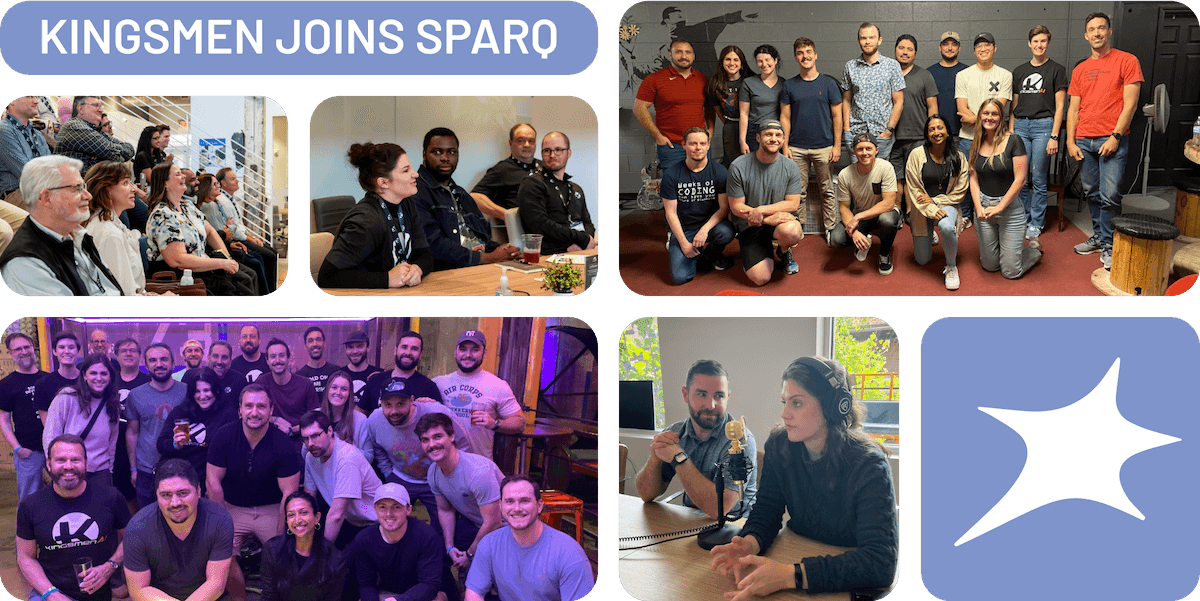

Same values, bigger mission

Kingsmen was recently acquired by Sparq.

We now have more diverse and broader skills with a much bigger team to scale with your business.

Naturally, as part of our transformation and merging process, we are moving! You can learn all about Sparq at teamsparq.com

It all starts here

Ready to bring your ideas to life?

As software consultants for key industry leaders, we’ve developed a highly trained eye to fully comprehend our clients’ needs and their users’ demands, so that we can develop the right solution for your business.